|

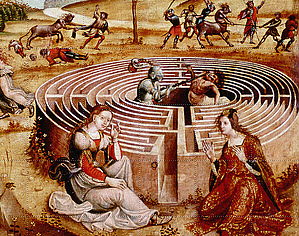

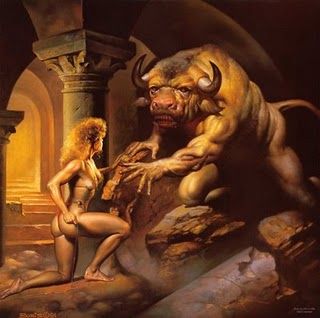

Okay, that’s probably not a viable franchise, more’s the pity, but I confess to an abiding love for these two stories. Each is horrific, almost repellent, yet is paradoxically fascinating and even erotic. As they’ve both been in my life for a long time, I’ve had the opportunity to notice similarities between the narratives and thought it would be useful to delineate seven themes, images and characteristics to show how a piece of classic mythology and a successful movie inhabit the same deep, viscerally imaginative space. 1. The Maze Both stories take place in a maze. In the tale of the Minotaur, the artificer Daedalus constructs a labyrinth to house the monstrous offspring of the beautiful Queen Pasiphae, who has been tricked by Poseidon into falling in love with a bull. Pasiphae’s husband is King Minos, who is the son of Zeus and thus a demigod; an example of the dual identities that inform characters in both stories. Minos, who is also king of Crete, cannot bring himself to kill the Minotaur and instead commands the defeated Athenians to send seven young, virginal men and women every seven years to be sacrificed to the monster in the labyrinth. In ‘The Terminator’, Los Angeles in 1984 is presented as an eerie, blue-lit grid with frequent dead-ends. It is harsh and unforgiving: the first inhabitants we meet are a homeless man and a gang of almost feral punks. Overlaying this physical complexity is that of time itself, which the characters are attempting to alter. Time travel narratives are notoriously hard to pull off, usually because the writers view alternative chronologies as mere settings rather than characters in themselves. ‘The Terminator’ gets around this shortfall by sheer savagery of intent; in other words, by embedding the story’s contradictions in the emotional make-up of its ferociously determined characters. 2. Sacrifice of the Innocents A lot of blameless people die horribly in both stories. The Minotaur, who is neither man nor beast, can only eat human flesh. The Athenians, who like the humans in ‘The Terminator’ are losers in a war they brought about, must send their young people to this horrible fate. Consider also that a young man or woman at that time was likely to be a teenager, if that, then picture them entering the gloomy, stinking maze to come face to face in the darkness with a raging, hungry bull-headed monster who then eats them alive and you can see why this story has stayed with me. Meanwhile, the Terminator kills a number of Sarah Connors before finding the right one, while numerous innocents from people at the nightclub to an entire police station are caught in the crossfire. Sarah herself is a naive, rather hopeless girl with awful hair who can’t even handle working as a waitress. She is unlucky in love and her one loyal companion is a pet iguana called Pugsley. As the audience, we take one look at the Terminator, one look at Sarah and think ‘this is going to be a short film’. Not only that, the Terminator isn’t even after Sarah for her own sake but for her role as mother to the messianic John Connor. In other words, the killer’s real target is a child who has yet to be conceived, let alone born. 3. Terrifying technology In ‘The Terminator’, humanity has created an artificial intelligence that comes to view its creators as a threat. Light, nuclear fire and burning play an essential role both in the setup of the film’s future, post-nuclear world and also in the revelation of the Terminator’s true form, after he is caught in an exploding oil tanker. Clanking garbage trucks, future tanks rolling over skulls, the red glow of artificial eyes - all of it is an overwhelming visual assault made beguiling by the skill of the storytellers. They are too clever to make technology wholly evil though: the Terminator is weirdly charismatic in his human form, while Sarah uses a hydraulic press to finish off her nemesis at the film’s climax. Technology functions as a metaphor for unthinking, powerful desire in the Minotaur story from its very inception. Minos is given a beautiful bull to be sacrificed in honour of Poseidon, but Minos wants the bull for himself and keeps it. An enraged Poseidon compels Minos’s wife Pasiphae to fall in lust with the bull and to enable the union the Queen has Daedalus create a wooden cow covered in cow skin (shades again of the Terminator and his coating of human flesh) with herself inside it. Here again we see multiple dualities: Pasiphae is the daughter of the god Helios and thus another demigod; like the Terminator, she uses a disguise as deception to bring about an ultimately destructive outcome. It doesn’t end well for Daedalus either. As he is the only one who knows the secret design of the labyrinth and thus the way out, he is shut up in a tower with his son, Icarus. Daedalus builds wings for himself and his son, using wax to hold the feathers together, and escapes by flight. Despite his father’s warnings, Icarus flies too close to the sun; the wax melts and Icarus falls to his death. Here again we see imagery based on fire, that most fundamental of human technologies, leading to hubristic catastrophe. That the artificial intelligence in ‘The Terminator’ is called ‘Skynet’ places it in the same physical realm as the ill-fated Icarus at his moment of maximum peril, while ‘net’ suggests yet further entrapment. 4. Convoluted family relationships ‘The Terminator’ wins out here, although only just. In the future, John Connor sends Kyle Reece back in time to save Sarah Connor. John knows that Kyle is his father and that Kyle will not survive. Kyle does not know either of these facts and neither does Sarah; indeed, the audience does not discover this tragic irony until the very end of the film. John Connor has the same initials as Jesus Christ, who is similarly sacrificed by his father for the greater good. While John is the son and Kyle the father, we sense that Kyle is the junior in their relationship as he is a loyal lieutenant to Connor’s leader. The ill-fated son/father relationship finds its reflection both in the fate of Daedalus and Icarus and also in that of Minos and the Minotaur. The latter’s name is derived from that of his step-father, who uses him as a weapon of terror to avenge the death in Athens of Androgeus, Minos’s birth son. That Androgeus is killed by a monstrous bull gives the story the same cyclical feel as the mind-bending time loops at the heart of ‘The Terminator’. But it is in the person of Sarah Connor, who is one of our great contemporary characters in any genre, that the family drama finds it best expression. Later ‘Terminator’ films explore Sarah’s relationship with John in greater and affecting detail, particularly the first sequel ‘Judgment Day’. In ‘The Terminator’, however, the relationship is only implicit, given maximum emotional weight as it is acknowledged at the very end of the film, with the mother’s terrible responsibility hinted at and all the more powerful for it. Meanwhile, Kyle’s adoration of Sarah has an almost religious intensity, especially given that his knowledge of her for most of his life is second-hand and that he only knows what she looks like because he has a single polaroid snap of her. Likewise, Queen Pasiphae has a quasi-religious identity: she is the daughter of Helios, god of - you guessed it - the sun. Both characters’ powerful sexuality and maternal instincts are suborned to a greater power play that is essentially patriarchal. Both Skynet and its machine empire feel brutally, efficiently male, while the Terminator himself with his incredible, muscular physique is an intense expression of masculinity at its most terrifying. Similarly, the Minotaur is a bull-headed man: the hybrid of a human with a notoriously strong and unreasonable male animal. 5. An unholy blend In each of the stories, it is the blend of improbable elements that create something memorably unpleasant. There is nothing wrong with a man and nothing wrong with a bull; it is the combination of both in a single being that upsets and beguiles. So, too, we have the cyborg Terminator, which is neither human or quite machine. James Cameron conceived of ‘The Terminator’ while suffering from fever, which is perhaps what lends the film its breathless, hallucinogenic intensity. Cameron sketched an image from his nightmare of a red-eyed chrome skeleton rising from the flames behind a young couple as they embrace. Here, perhaps, is the expression of an even deeper myth that lies behind both ‘The Terminator’ and the Minotaur stories: that of Death and the Maiden. Sarah Connor herself cycles through various mythic identities on her way to her true calling. She has elements in common with Queen Pasiphae, the warrior goddess Diana, the Christian Virgin Mary and the heroine of the Minotaur story, Ariadne. Sarah, the Terminator and the Minotaur are all servants of impersonal higher powers, from gods both machine and celestial to fateful time itself. 6. An extraordinary linking device In both narratives, there is a resonant physical linking device. In the story of the Minotaur, Minos has a daughter called Ariadne, who is put in charge of the labyrinth. One group of sacrificial Athenians includes Theseus, with whom Ariadne falls in love at first sight. She gives Theseus a sword to kill the Minotaur and a ball of thread with which to trace the route back out of the labyrinth. Ariadne’s thread is richly symbolic, representing constancy, love and rebellion. In ‘The Terminator’, Kyle Reese has a polaroid photograph of Sarah Connor, given to him by their son John. The photograph is as symbolic as Ariadne’s thread because it is taken when Sarah is talking to her unborn son about his father, who crossed time to save her. It is the first time the audience realises how the disparate chronological narratives of the story fit together. The photograph captures an incredibly romantic moment - seemingly hopeless, defiant and darkly funny. This temporal link is taken further with the introduction card to the film, in which we are told that the battle will be fought ‘tonight’, even though the night in question was in 1984 when the film was made. However many times I see ‘The Terminator’, that ‘tonight’ still delivers a visceral thrill, like Sarah’s photo. 7. The unknowable Finally, there is that unknowable quality in both strangely beautiful, frighteningly efficient antagonists. We will never know what the Minotaur thinks any more than we know what the Terminator thinks. We have hints, sly humour but mainly a fear of something physically overwhelming, wholly unreasonable and profoundly dangerous. It is why the stories are not really about these mysterious, fabulous monsters, although they are their tales’ most memorable elements. Instead, the stories of ‘The Terminator’ and the Minotaur are about the people whose lives they impact in such a unique and powerful way. Andrew Wallace is a novelist whose new science fiction thriller ‘Diamond Roads: The Outer Spheres’ will be published on 8 December 2016. www.andrewwallace.me

0 Comments

Recently I liked this far away three-pointer by Laurie Anderson and Lou Reed. They always struck me as adventurous storytelling characters, Super-people from the quiet wild side. Their quote was about finding ways to get through life. One: "Don’t be afraid of anyone. Now, can you imagine living your life afraid of no one?" Two: "Get a really good bullshit detector." Three: "Three is be really, really tender." “And with those three things” – Laurie said – “you don’t need anything else.” In the full wide range that stretches from street hobos to rich presidents and from Ivy-league dropouts to post-celebrity rehabs, there is a common thread: life is ripe with conflict. Sure, conflict is what made humans sharper, problem solvers until the last beat. Storytellers know that ultimately conflict alone can float identity through a sea of half-truths, up, up to the surface where the sun plays catch with flying fish. However important our culture of conflict may be, the search for less human pain, suffering, and crisis may also be a story to pursue. A peaceful target to shoot for. In dramatic movies, the ending may be, in terms of plot, happy or unhappy. In either case, if the story works, the viewer is rewarded with insights into the depths of human life. The ancient Greeks attended Tragedies more than school, feasting on pop-corn-less morality with cathartic heroes like Oedipus (an unknowing motherfucker) or universal strategists like Ulysses, king of the surprise climax. Endings in these stories didn’t seem to matter much. The deus ex machina finale at times gave Gods the task of resolving plot indecision or confusion. This over-the-top device released authors from spending too much stage-time on predictable closing show and tell details. (They lived happily ever after! was another shortcut). The middle of the story is where it all happened. Development, substance, focus, now. So, what can we learn about “making our life better” by watching a film story? It is true that caped Super-heroes are our cultural diet now, just as Commedia dell’Arte theatre masks were dominant wanderers from town to town for four centuries. Masks are types. Types embody in broad strokes the infinite relationships among standard folk: the rich man, the poor woman, the young lovers, the old doctor, the cop, the thief, the servant. It’s all about relationships, stupid. A film I would watch again is one that leads to my relationship with the story. Titanic was a lesson in teen-age blockbuster making, who would have thought it? Multiple viewings create a relationship, characters become familiar: it’s the key to the new TV series mania. Note for debate: Characters are not people, but they’re close enough to pretend. Characters stand in a story because the plot says so, and the writer cast them for a role. No script? No character. They look like people, however. Or should. This is not the case in real life where life may be scripted but in all likelihood is not very good. Determinists saw destiny play a bigger part than individuals. In the west we famously trust individual agency and will to drive success and failure. You want to be the big boss man? Slay the dragons. Dominate your universe and plunge forward. Action films seem equivalent to playing Mozart with only Major chords. (Male chords, duh) I have a preference for the Minor Key in film. Movies that don’t try and impress only with underlined cinematic cartwheeling. I have the same bias meeting people at parties. If a film reveals a personal insight, I am Up. If there is a label that explains everything or indicates next to each action, I am turned off. I follow film-makers that make movies that matter, even a little. As a producer of youth-cinema, I see film conflict not as a medieval head-to-head battle to release adrenaline, but a personal texture, an inside chess game of question marks: where to go? what to do? How? Who with? Well told conflict can be hesitation pure and simple. Or an identity short-circuit. Or lack of clarity, loss of vision. How to take direct action choices, then? Voting can be Hamletic too, in hard times. Even without a simple top-down final duel on a skyscraper, a film can lead to a character’s foggy melting point, the quiet intersection of dramatic need, desire and urgency in search of identity. Laurie Anderson and Lou Reed are not film characters. Their lingo is story with sound. They quest to stay away from trouble, they are grounded in their shape-shifting personae. Who they want to be? Simple: happier spending time together. Popcorn flicks too could explore that engagement vibe. In the script of life rewritten, I would try reducing, not adding, conflict to stories. Better conflict, of course, the one worth fighting for without fists and watching with senses aloft. As James Joyce said, the cinema is a “screen of consciousness”. Luckily I am not afraid of fear, I can smell bullshit from outside the playground, and I still want to hear my kids tell me I was kind. That’s a step towards a better now, even for a callous storyteller like me. There is already enough conflict to go around in the world. Danny Alegi is a filmmaker, story development coach and speaker. Read more of Danny's blogs at 'Movies Without Cameras'. |

Guest BlogWhere craftsmen and women share their thoughts on storytelling. Archives

January 2018

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed