|

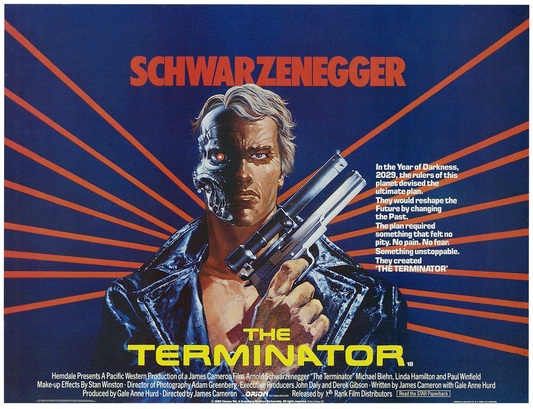

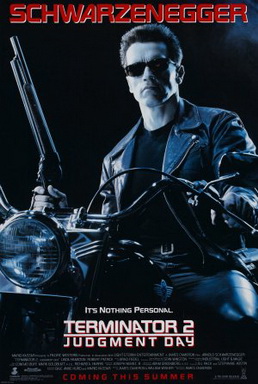

“You know, you were right,” my nephew said to me. “About what?” I asked. “Terminator is a better film than Terminator 2.” Finally, I thought. He had come to this revelation whilst being bedridden after an operation and watching James Cameron’s ‘The Terminator’ day after day. The debate as to which of Cameron’s killer cyborg movies is the best has raged since ‘Judgment Day’ was released in 1991. Of the 1652 people who voted in an IMDb Face-Off pole, 1206 chose ‘Terminator 2’; a survey of critics on Indiewire was split right down the middle; Terminator 2 is routinely cited along with ‘Empire Strikes Back’, ‘The Godfather: Part 2’ and ‘Toy Story 2’ as one of the few instances where the sequel is better than the original. The reasons why ‘Judgment Day’ is considered a superior film are that it has a better story, better effects and a better villain in the T1000. I must confess, I never thought ‘Judgment Day’ was equal to ‘The Terminator’ and the reason can be summed up in a single line of dialogue from each film. In ‘The Terminator’: Kyle Reese – ‘I came across time for you Sarah.’ And in ‘Terminator 2: Judgment Day’: The Terminator – ‘Now I know why you cry but it is something I can never do.’ At some point in the future John Conner gave Kyle Reese a photo of his mother and Kyle Reese became obsessed with it. Kyle tells Sarah about the photo, that he lost in a fire, and how he remembered every contour of her face and how he’d spend time wondering what she was thinking about at the moment the picture was taken. It turns out, at the end of the film, when a young boy in a petrol station takes the photo, what Sarah is thinking about is Kyle Reese. At its heart ‘The Terminator’ is a love story about two people who come together across time and create the messiah. The emotional heart of ‘Terminator 2: Judgment Day’ isn’t as sophisticated: through continued interaction with people, Arnold Schwarzenegger’s Terminator learns about empathy - something the people he and John Conner observe seem to have forgotten (‘It is in your nature to destroy yourselves’). ‘Terminator 2’ is essentially a machine’s coming of age story. But my nephew’s conversion made me think that maybe it isn’t a case of one film being better than the other but that the two films are for different times in a person’s life. When we are young, and the love of our close family is enough, we must learn how to empathise – to understand what other people are feeling and why – ‘Now I know why you cry but it is something I can never do.’ - but as we grow we all quest for love and hope that there is one person out there who will complete us because who wants to be alone – ‘I came across time for you Sarah.’ In a way, because it is a coming of age story, ‘Terminator 2: Judgment Day’ isn’t a sequel to ‘The Terminator’ but an emotional prequel. So if someone you know insists that ‘Terminator 2: Judgment Day’ is the better film and anyone who thinks otherwise is a fool (as my nephew used to), tell them to wait awhile because inevitably they’ll grow into ‘The Terminator’.

1 Comment

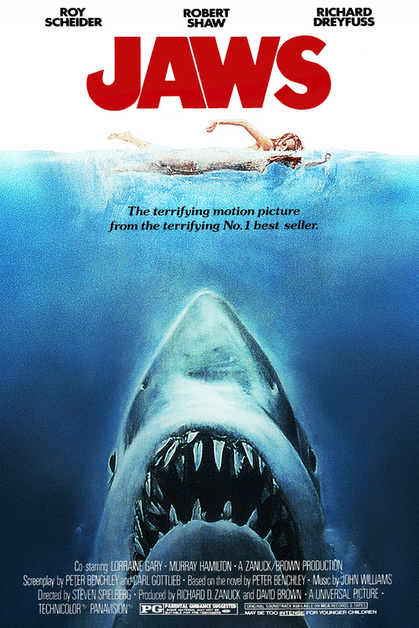

“First things first; Jaws is not about a shark.” film critic Mark Kermode wrote in the opening of his 2015 ‘Observer’ article ‘Jaws 40 years on: One of the truly great and lasting classics of American cinema’. Anyone familiar with Kermode’s BBC Radio 5 Live film show with Simon Mayo will know that he is fond of telling listeners what he thinks Jaws is actually about, namely infidelity. The question ‘what is a story about?'’ fascinates everyone because a story has to be about something. But there is a common lament amongst people who read manuscripts, books, plays and scripts for a living: ‘It was okay, but it wasn’t about anything.’ And that is clearly a problem. Kermode goes on to list various potential abouts that were debated at the ‘Jaws 40th Anniversary Symposium’ at De Montfort University in Leicester: ‘masculinity and crisis in Jaws’, ‘Jaws and eco-feminism’ and ‘Jaws: the case of the archetypal American villain as queer dissident attacking the heteronormative.’ These theoretical debates that take place once a story has been told are, of course, essential and interesting to academics but are completely and utterly irrelevant to a storyteller. So, for a storyteller, if Jaws isn’t about infidelity, which it clearly isn’t, and it isn’t about a queer dissident’s attack on the heteronormative, which is debatable, what it is about? To understand, you must first understand why we tell stories at all. Back in the days of yore, long before scholars set down the tales of Gilgamesh and Beowulf, the world was full of mystery and danger and the only way to make sense of the noises in the night or the lights that shot across the sky was to use your imagination. Those with the most fertile imaginations seemed to come up with the most plausible explanations: the noises in the night were monsters that would come and get you if you were bad and the lights in the sky were the creator’s anger. Over time, and through retelling, these seeds grew like any organic thing and became stories: the noises in the night became ‘Beowulf’ and the lights across the sky became ‘The Bible’. But what they never lost, in all the millennia they have been told and retold, is the germ of their inception: to make sense of the world. Whether they do it as a grand gesture – Tolstoy’s ‘War and Peace’ – or simple allegory - Orwell’s ‘Animal Farm’ – all storytellers continue to be motivated by this simple ambition. So what aspect of the world is Jaws trying to make sense of? Well Kermode is right in his opening statement: Jaws isn’t about a shark. The shark in Jaws has more in common with Melville’s ‘Moby Dick’ than it does to any real shark: it is vengeful and determined in a way that no real shark would be. So if it isn’t a real shark then it must be a monster, because it is terrifying and destructive like all good monsters are. And the universal truth about monsters is that they don’t exist. Monsters are always physical manifestations of the hero’s weakness and we know, because it is repeated throughout the beginning of the film, that Martin Brody’s weakness is that he is afraid of water. He is afraid, it is his defining characteristic, and when you look closely you realise that everyone around him is afraid of something: Hooper, the rich city boy, is afraid of not being taken seriously, the mayor is afraid of what will happen to his reputation and career if he closes the beaches, Ellen, Brody’s wife, is afraid of losing her family and the most wonderful manifestation of fear is Quint. Quint ends the monologue in which he describes watching his shipmates being eaten alive after a Japanese submarine sinks the USS Indianapolis with the statement that he’ll never put on a life jacket again: Quint is afraid of fear itself. In the first half of Jaws, Brody gives in to his fear: he remains on dry land while he gets others to hunt the shark. Halfway through, after the fishermen have caught the wrong shark and the patrol around the beach miss the shark because two boys cause a distraction, Brody realises that the only way he is going to defeat his foe is by following it into its lair – which is the thing he is most afraid of: the ocean. Once he is on the boat his fear is emphasised: he wears a life jacket and he refuses to climb out to the edge of the boat to give Hooper perspective. And things go from bad - ‘We’re gonna need a bigger boat.’ - to worse: Quint destroys their radio, the boat starts to sink, the engine explodes, they think they’ve lost Hooper when they pull his diving cage back up and it’s all mangled and then he has to watch Quint being eaten alive. All of which would traumatise any normal person never mind someone who was already afraid of water. And yet the experience has the complete opposite effect on Brody: instead of feeling that his fear was justified, his fear is vanquished: ‘I used to hate the water,’ he says, as he and Hooper swim back to dry land. ‘I can’t image why,’ Hooper responds. We are all afraid of something – whether it is an irrational fear like being afraid of water, a contemporary fear such as not being taken seriously or losing our job, or a primal fear like losing our family – and the only way we can overcome our fears is not by giving in to them or letting other people deal with them but by facing them. That’s what Jaws is about: fear and how we overcome it. |

ScriptPlayerWriter, reader, pontificator. Archives

May 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed