|

“So many set out to write a script; so few set out to tell a story.” This was a sentiment I expressed at a meeting of the department heads, the exec producers and the readers at the BBC Writersroom. When I worked at the Writersroom we spent days sifting through radio dramas, theatre plays and screenplays for film and television. One thing became very clear very quickly: whilst people had a passion to write scripts, they didn’t seem to have an equal passion to learn what a story is and how to tell one. These two questions form the bedrock of the MA Performance: Writing course at Central Saint Martin's: what is a story? And how do you tell one? Students on the course can expect to watch and listen to stories in many different media: film, TV, theatre, web series, interactive, audio; they can expect to hear stories from other students who come from all over the world; and they can expect to be taught by working professionals whose job it is to tell stories. Students will work on their individual projects; they will collaborate with others on the course; and they will collaborate with other courses. Students will be expected to engage in self-directed learning: watching, listening and reading stories outside their usual sphere of interest, making use of the library, presentations and talks delivered by industry professionals. And throughout it all every student will be expected to engage with the questions: what is a story and how do I tell one? Year 1 of the course is tutor driven. In Unit 1 students will explore storytelling in television, theatre and digital media (web series and interactive). In Unit 2 students collaborate with the MA Character Animation students as well as write a short film script. Tutors will share their views of storytelling, their experiences of working across various media and inspire students to challenge themselves. Year 2 is student driven. Unit 3 is comprised of Professional Prep and a student led Symposium. In Professional Prep students explore their place in the storytelling industry – which creative outlets would suit their voice and how to approach them. Or create their own by setting up their own social media channel or theatre company. The Symposium allows each student to explore some essential aspect of storytelling that inspires, fascinates or challenges them. In Unit 4 students work on their final portfolio and take on the role of script editor or dramaturg to each other’s writing.

Throughout students are expected to engage with the questions what is a story and how do I tell one? There is no expectation that the answers to these questions should stay the same over the course of the MA, nor that there is a single answer that applies to all students universally and certainly not that the stories of one culture are more important than the stories of another. Nor that a story told in an interactive text-based adventure should be the same as a site-specific theatre experience. And definitely not that the narrative theories of any one thinker are more relevant than any other. The only expectation is that when each student sits down to work they are sitting down to tell a story and not sitting down to write a script. Find out more at: MA Performance: Writing at Central Saint Martin's

1 Comment

“Following the latest advice from the Government, Light House has taken the difficult decision to suspend our programme indefinitely, with our last screenings taking place today, Thursday 19th March 2020.” This is the message posted on the website of my local independent cinema. A similar message, in hundreds of languages, probably appeared in cinemas all over the world as the lights went out throughout February and March. The Light House is my favourite place to watch films. It’s a multipurpose building with a small gallery for local artists to display their work, a friendly café/restaurant and a courtyard where bands sometimes play in the evenings. They have two screens: a large 240-seater and a 67-seater Studio Cinema. It’s in that smaller screen you’ll usually find me, enjoying a mid-week matinee with a discounted coffee. It’s basically a large room, with no rake, a small screen but a full digital sound system. I sit right at the front, right in the middle and usually there are only a few other patrons dotted around. It’s in the Studio Cinema that I watch those hard to see films that no one else will be screening, like Hope Dickson Leach’s bleak ‘The Levelling’ or Alice Rohrwacher’s wonderfully strange ‘Happy as Lazzaro’. But I’ll head there to see the Hollywood blockbusters too – it was in that little screen that I saw ‘Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker’, Rian Johnson’s ‘Knives Out’ and it was the perfect setting to take my teenage, horror-obsessed, son to see John Krasinski’s ‘A Quiet Place’. Apart from the occasional visit with my son or my partner, I’m at that stage now in my cinema going evolution where pottering off to see a film by myself is natural. It wasn’t always that way, of course. When I was young, I went with family: to watch Hollywood films like the re-release of Disney’s ‘The Jungle Book’ or Spielberg’s ‘E.T.’ and Robert Zemeckis’ ‘Back to the Future’ at the ABC Cinema which was so big it had an upstairs balcony. Occasionally we’d go to see a Bollywood film which were so long there would be an interval and we’d pop out to buy a samosa. Then came the teenage years, a group of friends and the summer of 1989. Those who were there remember it fondly because it seemed like every week there were a couple of must-see films you just had to see! ‘Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade’, ‘Lethal Weapon 2’, ‘See No Evil, Hear No Evil’ and, of course, Tim Burton’s ‘Batman’ – we were teenage boys, after all. Maybe the anticipation of ‘Avengers: Infinity War’ and ‘Avengers: Endgame’ comes close to capturing the frenzied excitement that surrounded ‘Batman’ that summer. We were so eager to see it that we even contemplated queuing at 6am to make sure we got a ticket – that was back in the day when you had to stand outside to make sure you got in. In the end we opted to queue for four hours. Then a multiplex, which promised no adverts (that didn’t last long) and no queues (that was only partially true), opened a 30 mins bus ride away. That became our favourite haunt every Saturday night and we watched everything: our minds were blown by Oliver Stone’s ‘JFK’ and Spike Lee’s ‘Malcolm X’, we sat in awe at James Cameron’s ‘Terminator 2: Judgement Day’ and we debated for hours whether the events in Paul Vehoeven’s Schwarzenegger starring ‘Total Recall’ had actually happened. Then another multiplex opened, Cineworld, much closer to home and it was there that I saw ‘Jurassic Park’, ‘The Shawshank Redemption’, ‘Forrest Gump’ ‘Toy Story’ and ‘The Matrix’ for the first time. After that I moved to Newcastle-upon-Tyne to study filmmaking and the Tyneside Cinema became a regular haunt. It was there that we saw the films of exciting new directors like Quentin Tarantino with ‘Reservoir Dogs’, Peter Jackson with ‘Bad Taste’ and Danny Boyle with ‘Trainspotting’. It was there that I started to watch European films with the release of Jean-Jacques Beineix’s director’s cut of ‘Betty Blue’. And it was also there that I contemplated walking out of a film for the first and only time: those of you who have seen Louis Malle’s ‘Damage’ will know how excruciatingly painful it is. Then, post-university, there was time spent frequenting the Electric Cinema in Birmingham where you could get a slice of cake to take in with you and after that the Genesis Cinema in the east end of London where Tuesdays were discount days and invariably sold out – especially when you wanted to see something like Sam Rami’s ‘Spider-man’ or Spielberg’s ‘Minority Report’. After that I moved to France and the local Katorza cinema became a cinematic lifeline because it showed films in version originale (VO) instead of the dubbed versions (VF) you’d find at the local multiplex (although returning now I’m surprised to see that the French obsession with dubbing films has waned somewhat as VO screenings are popular in the multiplexes). It was in Screen 1 that I saw out the Lord of the Rings trilogy, the middle films of the Harry Potter franchise and the beginning of the MCU. I’d drop my son off at school, work in the mornings and then head there for an afternoon screening before returning to pick him up. That’s how I saw Mira Nair’s ‘The Namesake’ and Paul Thomas Anderson’s ‘There Will be Blood’. I also sat through David Lynch’s ‘Inland Empire’ and struggled through ‘Le voyage de Chihiro’ (Spirited Away) in Japanese with French subtitles and Almodovar’s ‘Volver’, Spanish with French subtitles. French cinema, funded by the government, was very domestic because there wasn’t a thriving television drama sector as there is now but Guillaume Canet’s ‘Ne le dis a personne’ and Jean-Pierre Jeunet’s ‘Un long dimanche de fiancailles’ were captivating. My first experience of ‘The Incredibles’, ‘Finding Nemo’ and ‘Cars’ was to see them in French with my son at the Gaumont. And there was also Le Cinématographe, the ultimate art house cinema, where I took by son for his first screening and post-show discussion with a writer/director: Michel Ocelot with ‘Azure & Azmar’ and introduced him to the genius of Harold Lloyd in ‘Monte là-dessus!’ (Safety Last). Then it was back to England to study for an MA at Goldsmith’s College and ‘Avatar’ at the IMAX in 3D (not a great film and nor was I impressed with the 3D – but boy, oh boy you had to be inspired by Cameron’s imagination!) Ever since then I’ve lived all over the country, dipping in and out of cinemas wherever I end up: Home in Manchester, the Watershed and Cube in Bristol and any number of cinema’s dotted around London, Birmingham and Cardiff. I always hunt out those pleasant oddities such as Ali Abbasi’s ‘Gräns’ (about a woman who discovers she’s half troll) and Jonathan Grazer’s ‘Under the Skin’ (about a woman who’s really a predatory alien) but I also enjoy a good Hollywood spectacle. Which brings us to Kevin Feige and his MCU. Of course some in the audacious Infinity Saga were underwhelming – ‘Thor 2: The Dark World’ – and some were just okay – ‘Ant-Man’ – but others were great films: ‘Ironman’, ‘Captain America: Winter Soldier’, ‘Captain America: Civil War’, ‘The Guardians of the Galaxy: Vol 1 & 2’, ‘Black Panther’ and ‘Thor: Ragnarok’. And if you’ve been going to the cinema as long as I have, if you’ve watched as many films and their sequels as I have and if you’ve been disappointed at the unfulfilled promise of an epic finale as I have, then you’ll know that what Feige, the Russo brothers and the writers, Christopher Markus and Stephen McFeely, achieved with ‘Avengers: Infinity War’ and ‘Avenger: Endgame’ is unprecedented. I saw ‘Avengers: Endgame’ seven times at the cinema, in six different cities, in two different countries and in virtually every format it was released in, and in every screening people laughed, people cheered and at the end, when Robert Downey Jr’s Ironman snaps his fingers causing Thanos and his army to ash away and then collapses, all you could hear were the people who were crying.

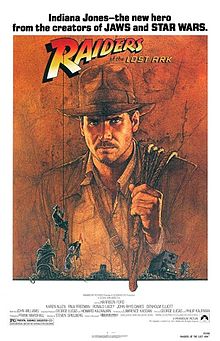

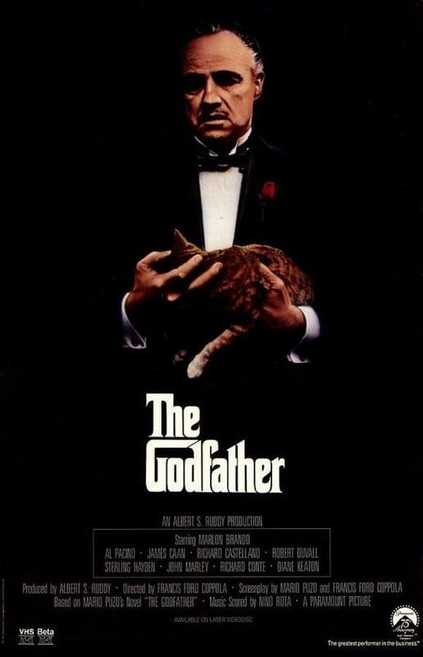

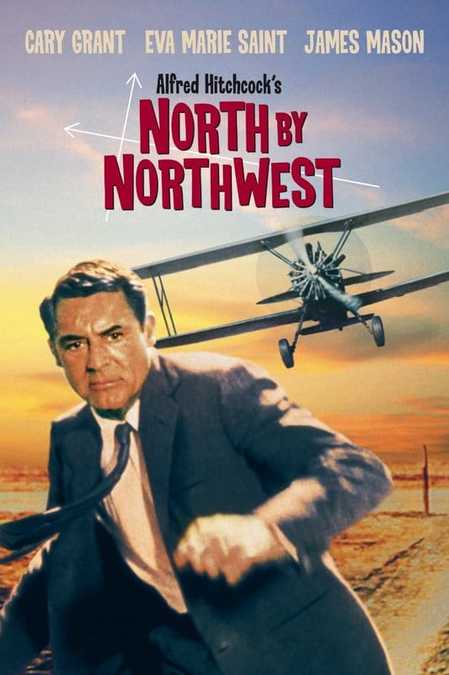

That is a story told. And that’s cinema. As was the poignancy in Hirokazu Koreeda’s ‘Shoplifters’, the heartache in Pawel Pawlikowski’s ‘Cold War’, the corrupted innocence in Taika Waititi’s ‘Jojo Rabbit’, the pain and determination in Greta Gerwig’s ‘Little Women’ and, of course, the social pestilence in Bong Joon Ho’s ‘Parasite’. So, when the cinemas open their doors again and the lights go down again, this time at the beginning of the screening, I’ll be right there, just as I have always been, to be captivated by that magic lantern show. “Here’s my jaw, drop it." “All right: Indiana Jones plays no role in the outcome of the story. If he weren’t in the film, it would turn out exactly the same…the Nazi’s would have still found the ark, taken it to the island, opened it up and all died. Just like they did.” ‘The Big Bang Theory’ fans amongst you will remember this exchange between Sheldon Cooper and his long-suffering girlfriend Amy Farrah-Fowler, and how, in a matter of seconds, she unpicks one of his favourite films and destroys it for both him and the show’s other regulars. There have been many impassioned rebuttals of Amy’s critique of ‘Raiders of the Lost Ark’: people point out that if it wasn’t for Indy the Nazi’s would never have found Marion; if it wasn’t for Indy the ark would have been loaded onto a plane and flown straight to Berlin; if it wasn’t for Indy telling Marion to close her eyes they would both have been killed at the end. But as Sheldon, Leonard, Rajesh and Wolowitz discover as they try to find holes in Amy’s logic, she is, in fact, right: when Indian Jones enters the story, the Nazi’s have already found Tanis, the lost city where the ark is hidden, and they are already in search of Abner Ravenwood who possesses the head-piece to the staff of Ra. Perhaps the best we can say of Indiana Jones’ role in the plot of ‘Raiders of the Lost Ark’ is that he delays the inevitable. Not a ringing endorsement for the main character of a plot driven action film – the same cannot be said of other 80s action heroes: John McClane in ‘Die Hard’, Schwarzenegger’s Dutch in ‘Predator’ or Ripley in ‘Aliens’. What, then, of Indy’s nemesis René Belloq? Is he more integral to the plot? The answer would seem to be no, he isn’t. In the entire film Belloq performs two actions: he takes the fertility idol off Indy at the beginning and he opens the ark at the end. Even Steven Spielberg, in a recorded discussion with George Lucas and Lawrence Kasdan, in which Lucas outlines the story of ‘Raiders of the Lost Ark’ that he had been working on with Philip Kaufman some years before, points out: ‘There’s no confrontation now with the arch-rival.’ And there isn’t – the closest we get is Belloq convincing Indy not to blow up the ark. In Kasdan’s early scripts Indy and Marion salvage the ark and then escape from the Nazi’s in a mining cart through an elaborate series of tunnels (a sequence that was resurrected for ‘Temple of Doom’). But none of that is in ‘Raiders of the Lost Ark’ and Belloq had already opened the ark and been killed by the time they salvage it. Hard to imagine that ‘Die Hard’ would not end with a final confrontation between John McClane and Hans Grubber, or that the climax of ‘Predator’ was not Schwarzenegger going toe-to-toe with the Predator, or that Ripley would not confront the alien queen with the immortal line: ‘Get away from her, you bitch.’ It is one of the most fundamental laws of storytelling that if there is a clearly defined hero and an equally clearly defined villain they will meet at the end and, nine times out of ten, the hero will emerge victorious. Yet, this isn’t how ‘Raiders of the Lost Ark’ ends. Or is it? Another debate that has raged, and one that is closely linked to Indy’s role in the plot, is whether god arriving at the end of the film and killing everyone whilst Indy is tied to a pole, constitutes a deus ex machina. The deus ex machina is considered the bane of any good storyteller and story: it implies an ill-thought-out plot that can only be resolved by the sudden introduction of an inexplicable contrivance. What sets ‘Raiders of the Lost Ark’s potential deus ex machina apart from all other examples since the ancient Greeks is that it is literally the sudden arrival of god – who metes out vengeance and then leaves. Some argue that god’s cameo is not a deus ex machina because it is appropriately foreshadowed: both Marcus Brody and Sallah warn Indy the ark isn’t something to be meddled with and that it contains ancient, mysterious powers. Indy goes from being someone who doesn’t believe in the bogyman to someone who accepts there are powers he cannot understand which is why he tells Marion to close her eyes: he has grown as a character. The problem with this argument is that Indiana Jones is going in search of the lost ark of the covenant, the adorned box containing the stone tablets upon which the 10 commandments were written that Moses brought down from Mount Sinai after speaking to God. For Indiana to go on such a quest he must believe, at the very start of the story, that everything that happened in the Old Testament of the Bible is the literal truth – which means he could equally have gone on a quest to find Noah’s Ark or the burning bush or the pillar of salt which was all that remained of Lot’s wife after she did look. Not a man, then, who is completely immune to the fantastical. A more accurate reason why god’s sudden arrival at the end of ‘Raiders of the Lost Ark’ isn’t a deus ex machina is that god is the antagonist of the story. God hid the ark by causing a sandstorm that lasted for a whole year and clearly wants to keep it hidden. The Nazi’s are the protagonists of the story: they are the ones who are driving the action in their quest to find religious artefacts. The story ends, as all such stories do, with a confrontation between the antagonist and the protagonist, in this case between good and evil. And good wins. So, if Indiana Jones and René Belloq are neither the antagonist nor protagonist in a story about finding the lost ark what story are they the protagonist and antagonist in?

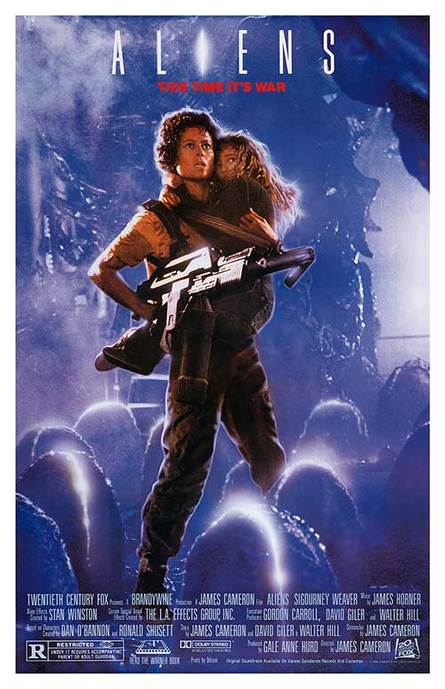

The clue, of course, comes in Belloq’s first words to Indy: ‘Dr Jones, again we see there is nothing you can possess which I cannot take away.’ Indiana Jones’ struggle is to have something that René Belloq can’t take away from him. For the longest time Indy thinks it is the ark – but the battle for the ark is a struggle between a symbol of pure good and the embodiment of pure evil: it is too titanic a battle for mere mortals. Instead, Indy and René are the antagonist and protagonist in the story of a work-obsessed adventurer who is forced to team up with his old girlfriend to find the lost ark only to realise that she is more important to him than it is. René is the protagonist: he is actively trying to seduce Marion; Indy is the antagonist: he feigns indifference but is really burning with jealousy. The mid-point of ‘Raiders of the Lost Ark’ isn’t Indy discovering where the ark is; it’s him discovering that Marion is still alive. In the climax René thinks he has everything, the ark and Marion, but Indy realises that only Marion is important. It doesn’t matter that the Nazis would have found the ark without Indy; it doesn’t matter that he only ever has the ark briefly before the Nazis take it away from him; and it doesn’t matter that he never gets to take it to a museum to study it. All that matters is Marion – her smile, the pain when he thinks he’s lost her, the envy he feels when he sees the dress René gives her, and the joy he feels at the end when she threads her arm through his. What Indiana Jones finds at the end, that no one will ever take away from him, is Marion’s love. Amy Farrah-Fowler’s mistake was to think that ‘Raiders of the Lost Ark’ is about a man who needs to find a lost ark. ‘Never explain anything; always imply everything.’ Mr Wootten, English teacher. Few lessons from school have stuck with me as profoundly as that single sentence spoken to me by my high school English teacher. Of course, being a cock-sure teenager at the time, I didn’t understand what he meant: surely as a storyteller your job is to build a coherent and fully functioning world, to populate it with perfectly imagined, three dimensional characters and to construct a watertight plot…? At least that's what I thought. And then I watched Stanley Kubrick’s ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’. When you’ve grown up watching ‘Buck Rogers in the 25st Century’ and ‘Star Trek’ on TV and being dazzled by Spielberg’s ‘Close Encounters of the Third Kind’ and Lucas’ ‘Star Wars’, the first time you watch ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’ – if you manage to make it through to the end – your initial response is ‘What the hell was that about!?’ From the opening Dawn of Man sequence with the arrival of the inert monolith, to the balletic movement of ships in space, the secrecy surrounding the discovery of an object on the moon, the trip to Jupiter and Hal’s malfunction, Bowman’s rapid ageing and finally the baby floating in space – on first viewing none of this made any sense to me at all. What was the monolith? Where had it come from? Who’d built it and what did it say to Star-watcher, the ape, that inspired him to pick up the bone and use it as a tool and then as a weapon? And the eerie sequence on the moon where another monolith is discovered – or is it the same one? And if it is, who buried it? – and suddenly it emits a high frequency radio signal aimed at Europa, one of Jupiter’s moons. What is it saying? Who is it talking to? And then there’s Hal, a 9000-series computer, machines that have never made a mistake, and yet he malfunctions, murders Poole and tries to kill Bowman. Why? And finally Bowman falls into the infinite – what the hell is that? – and watches himself age – is this really happening or is it in his head? And then he’s reborn - ? – as the Starchild - the next stage in humanity’s evolutionary journey? I’d never seen a film before that seemed to raise so many questions without giving an answer to any of them. ‘That’s the magic of this film, that nothing is tied up neatly…it’s what isn’t said and explained that is part of its mystery. And maybe Stanley didn’t know 100% himself.’ said Keir Dullea, who played Bowman, in the documentary ‘2001: Making of a Myth’. It seemed that ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’ was the very definition of what Mr Wootten had been trying to tell me. If you look hard enough you do start to find answers in the many makings of documentaries and the 1984 sequel ‘2010: The Year We Made Contact’: initially the monolith was going to have a screen on it which, presumably, would have shown Star-watcher what a tool was but Kubrick preferred it to be seamless; the monolith on the moon was an alarm system that would be triggered when humanity had advanced sufficiently to escape the Earth and was taken from Arthur C. Clarke’s short story ‘The Sentinel’; Hal malfunctioned because he knew Discovery’s mission but he had to pretend to the crew that he didn’t: he had to lie; and the original concept for the finale was that Bowman would meet the alien race that had created the monolith but Kubrick ran out of time and money so had to come up with something else. None of this is made explicit in the film and some are only partial answers. And the more you watch ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’ the more you realise that it is the holes, the mysteries, that keep drawing you back because maybe somewhere in the mesmerising visuals there is an answer. But then you remember Dullea’s words that even Kubrick wasn’t 100% sure himself. This idea that the storyteller doesn’t need to be 100% sure of her own story was echoed by screenwriter Eric Heisserer in an interview with Jeff Goldsmith. He explained that whilst adapting Ted Chaing’s short story ‘The Story of Your Life’ into ‘Arrival’ one of director Denis Villeneuve’s instructions was that there had to be a mystery in the story that not even they could explain: why twelve spaceships and why do they stop where they do? There are many films with compelling mysteries that latch into the viewer’s mind and just won’t let go: in ‘Close Encounters of the Third Kind’ why are the people who feel driven to find Devils Tower, Wyoming invited by the aliens? in ‘Alien’, who is the Space Jockey and what planet did he visit to harvest the xenomorph eggs? in ‘Memento’ who killed Leonard’s wife? in ‘Blade Runner’, is Deckard really a replicant? When an answer is given to these questions – as ‘2010: The Year We Made Contact’ and Ridley Scott’s alien prequels try to do – they are never satisfying because they set out to explain what was implied. And If you explain everything you lock the audience out of the story but if you imply everything you feed their imagination and the story becomes theirs. “I don’t know if we each have a destiny or we’re all floating around, accidental like, on a breeze. But I think maybe it’s both. Maybe both is happening at the same time,” says Tom Hanks as Forrest Gump as he tries to unpick the eternal conundrum of fate verses free will. His ruminations have a lot in common with a struggle writers have when they start a new story, something that was made clear to me recently when I took a class in writing a one-hour TV pilot: is the story character driven or plot driven? Or is it a bit of both? Most of the students seemed to think their stories were a bit of both. But then we watched the openings of four different UK television dramas and the students easily identified which were character driven stories and which were plot driven – then, when they looked at their own stories again, the ambiguity had gone. This distinction wouldn’t have been as easy if I’d shown them ‘Forrest Gump’. A character driven story is defined as a story in which the internal emotional journey of the main character is more important than the external plot. There are many great character driven stories: ‘It’s a Wonderful Life’, ‘The Shawshank Redemption’, ‘American Beauty’ to name a few - but one that stands out is Francis Ford Coppola’s ‘The Godfather’. While the turf war between five competing Sicilian families is important and the choice whether or not to enter the narcotics trade plays a key role, the story is about Michael Corleone. It is Michael’s transition from patriotic war hero to head of an infamous Mafia family that keeps us watching. What Michael, played by Al Pacino, wants at the beginning of the story is to be unlike his family, he makes this explicit to his girlfriend Kay, Diane Keaton, at his sister’s wedding. What Michael needs is to realise the very characteristics that made him go against his family’s wishes and go to war – his sense of duty, honour and integrity - are the very traits that will make him the perfect Godfather above his hot-tempered older brother, Sonny, and his cowardly middle brother Fredo. Sitting at a table in a restaurant in the middle of the film facing the two men who are trying to kill his father he has a choice: walk away and do what he wants to do and not be like his family or do what he needs to do, which is kill them, and start upon the road that will lead him to be the Godfather. Like any story that ends well, he gives in to his need: he stands and shoots them both dead. This ability to define a character’s conscious and subconscious desire clearly isn’t possible with ‘Forrest Gump’ because Forrest Gump seems to want and need the same thing: to be with Jenny – but, as discussed in the first part of this blog, he makes no attempt to be with her and soon after she has acquiesced to be with him, she dies. So is it a plot driven story? A plot driven story is a story in which external events are more important than the main character’s internal, emotional journey: Indiana Jones is the same person at the end of ‘Raiders of the Lost Ark’ as he is at the beginning; Jack Ryan is the same, noble man in every film he appears in no matter which actor is playing him and Miss Marple incisively tracks down killers across decades in TV and film and never once comes to a moment of profound self-revelation. The most pristine example of a plot driven story is Alfred Hitchcock’s ‘North by Northwest’. In it Cary Grant plays Roger Thornhill, a suave New York advertising exec, whose only weakness is his mother. Sitting in a hotel restaurant Thornhill sticks his hand up to attract a waiter’s attention just as a message is broadcast over the PA system asking for a George Kaplan. Two enemy agents, who have been staking out the hotel, think Roger has identified himself as Kaplan. From that moment until the end of the film Thornhill’s life is in danger as he tries to discover who Kaplan is and why everyone seems to think he is Kaplan. He is almost driven off a mountain road, he has to dodge a crop duster that is ‘dustin’ crops where there ain’t no crops’ and in the end he almost slides off Mount Rushmore. But at no point does his conscious and subconscious desires collide and he is the same suave, sophisticated exec at the end pulling Eva Marie Saint into the top bunk as the train they are on penetrates a tunnel, as he was at the beginning. Whilst Forrest Gump is exactly the same person at the end of the film sitting by the bus stop waiting for his son to return from school as he is in the first flashback where he remembers his first pair of shoes, the film has no mystery that needs to be resolved or any danger that need to be eluded. There is no plot. Forrest meanders from one defining moment in US history to another with absolutely no plan. And the film isn’t building up to a particular climax that has been intricately established and developed over the course of its two hour running time. So ‘Forrest Gump’ isn’t plot driven nor is it character driven and it doesn’t fall into that liminal zone that most writers seem to think their stories exist where it’s a bit of both – it is a lot of neither. It is essentially a series of vignettes strung together by Forrest’s love for Jenny. So it shouldn’t work as a story. But on that October evening back in 1994 when I went to see ‘Forrest Gump’ on its opening weekend I was struck by the reaction of the woman sitting next to me. From the moment the feather appears in the opening credits to when it appears again at the end, she was enraptured. Mostly she sat in silence but there were times when she laughed – on seeing the expression on Jenny’s college room-mate’s face as Forrest and Jenny make out on the bed behind her – and there were other times when she cried – when Forrest returns home because his mother is dying or when Lieutenant Dan finally thanks Forrest for saving his life. I thought then, and I still think now, that a story that can sweep someone up so completely that it can make them laugh and cry is quite some story indeed - whether it adheres to a template of what a good story should be or it doesn’t. “But I have been too deeply hurt, Sam. I tried to save the Shire, and it has been saved, but not for me. It must often be so, Sam, when things are in danger: someone has to give them up, lose them, so that others may keep them.” says Frodo at the end of J.R.R. Tolkien’s ‘The Lord of the Rings’. “How do you pick up the pieces of an old life?” ponders Elija Wood as Frodo as he wanders around Bag End listlessly at the end of Peter Jackson’s ‘The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King’. Frodo’s musings work perfectly within the context of ‘The Lord of the Rings’: forced to leave the innocence and comfort of Hobbiton to travel across a world into the scorching hell of Mordor; after having witnessed unimaginable suffering and having suffered himself; over the course of almost a 1000 pages in the book and over 10hrs of screen time in the films (the cinematic versions not the extended DVD editions), we empathise with Frodo’s struggle to fit back in when he returns to the quiet routine of his home. But the passages have a deeper resonance for those who know because it is impossible to read/hear either of them and not think about what inspired them: Tolkien’s experiences in the First World War and the disconnect the soldiers who survived felt when they returned home. There are many allusions to WWI in ‘The Lord of the Rings’: the rising threat of danger and destruction amassing in the East as Sauron assembles his armies mirrors the rise of Germany; the decimation of natural forests to build factories to service the war effort around Isengard was what Tolkien witnessed happen to the countryside around Birmingham; the alliance of many people from different countries speaking different languages coming together to fight a common foe in Sauron equates to the alliance of Russia, France and the UK against the alliance of Germany and Austria-Hungary ; the talk of how the War of the Rings will be the great war to end all wars echoes what most thought about WWI when 70 million troops where mobiles and 16 million people died. Much has been written about ‘The Lord of the Rings’ and its use of metaphor, specifically allegory. Tolkien himself had this to say in the forward to the second edition of ‘The Lord of the Rings’: “I cordially dislike allegory in all its manifestations, and always have done so since I grew old and wary enough to detect its presence. I much prefer history – true or feigned– with its varied applicability to the thought and experience of readers. I think that many confuse applicability with allegory, but the one resides in the freedom of the reader, and the other in the purposed domination of the author.” So Tolkien never explicitly set out to write about the war in an allegorical way, as Orwell set out to write about a totalitarian state in ‘Animal Farm’, but he accepts that as readers we might look at Frodo’s journey through that lens: the truthful rendering of an experience many found indescribable: having to abandon their homes to travel to faraway places to fight a remorseless enemy and witness unimaginable scenes of horror and destruction. Whereas Tolkien seems reluctant to accept his use of metaphor, others embrace it: Paul Verhoeven has described how his 1987 film ‘Robocop’ is a retelling of Christ’s story, Steven Spielberg has talked about how E.T in his 1982 film is really a father figure who steps in when Elliot’s real father has left (in one scene E.T. even dresses up in a man’s clothes and gets drunk whilst watching TV) and Neill Blomkamp accepts that it was apartheid blighted Johannesburg that inspired ‘District 9’. One of my favourite uses of metaphor is in James Cameron’s ‘Aliens’. “The national psyche was still full of Vietnam so I think that, because Jim was going to do it all with colonial police kind of thing, there should be a subliminal Vietnam look.”

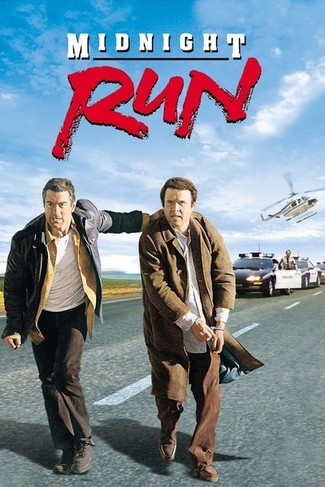

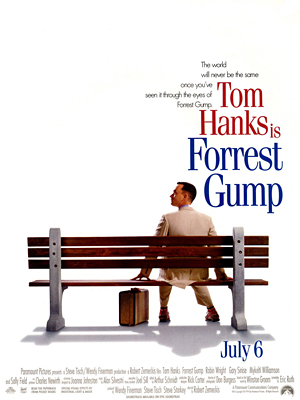

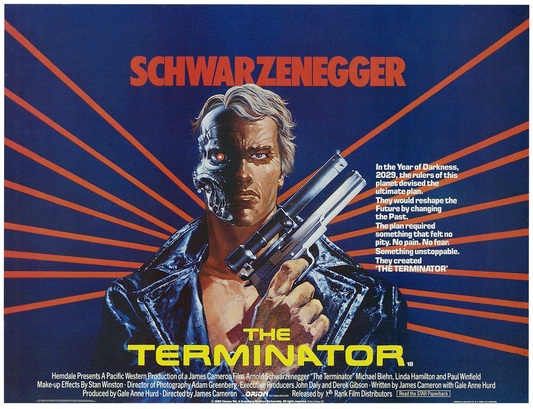

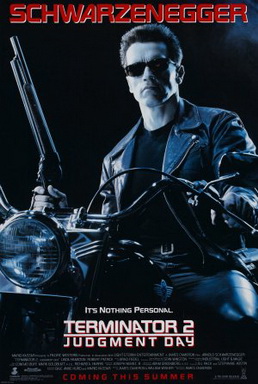

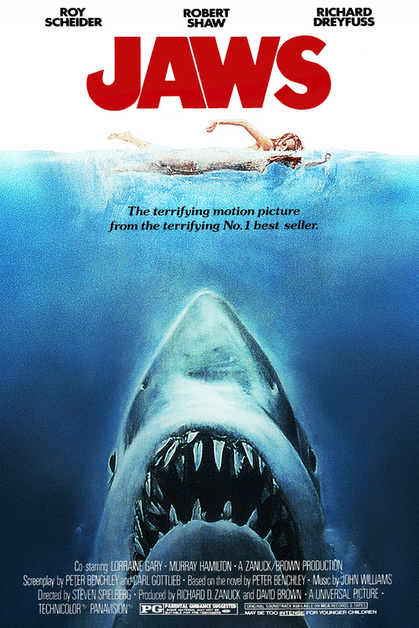

says the inspirational Ron Cobb who worked as the conceptual artist on the film. Once you know that ‘Aliens’ is a metaphor for the Vietnam War you see the similarities everywhere: the insidious corporation that sends a group of highly trained, gung-ho marines into battle against a less equipped but determined enemy. How the marines’ initial optimism quickly turns to despair as their numbers are decimated. How they become resentful and disillusioned when they realise they were sent to war not for a noble purpose but to service the corporation. And how, in the end, the only survivors are the ones that knew the war was wrong and unwinnable from the beginning: Hicks, the cynic, Newt, the innocent victim, and Ripley, who tried to warn everyone from the start. Once you start looking for it you can find metaphors, intentional or unintentional, everywhere: in the adventures of Harry Potter; in the dark corners of any good horror story; in the battles between superheroes and super-villains. C.S. Lewis, Tolkien’s friend, once wrote: “The function of allegory is not to hide but to reveal, and it is properly used only for that which cannot be said, or so well said, in literal speech. The inner life, and specially the life of love, religion, and spiritual adventure, has therefore always been the field of true allegory; for here there are intangibles which only allegory can fix and reticences which only allegory can overcome” (Lewis, Love 166). Maybe that is why sci-fi and fantasy tackle the big issues of war, despair and political intrigue. Lewis’ Chronicles of Narnia are seen as a reimaging of the Christian myth – which is, as Joseph Campbell revealed, just a reimagining of an ancient universal myth. Which brings us back to ‘The Lord of the Rings’ because it is also a retelling of the mono-myth. So even though he was set against it, Tolkien layered metaphor upon metaphor as he expressed his pain and the pain of many thousands of others in one of the greatest feats of imaginative storytelling. He wrote about what he knew but didn’t constrain his imagination to what he’d seen. And a good metaphor, used intelligently, is what great storytellers always use to allow their imaginations to soar. “We have never not gotten the note that we need to raise the stakes. ‘Raise the stakes’ is what every executive must learn on the first day of executive school.” said Rhett Reese on the excellent Q&A with Jeff Goldsmith. He, along with his co-writing partner Paul Wernick, were discussing the tortuous six year journey it took to get ‘Deadpool’ to the screen. Unlike most Marvel superhero films where the stakes are raised until the entire planet is under threat and only one (in the case of the standalone adventures) or most (in the case of the Avengers and X-men films) superhero/es can save the day, ‘Deadpool’ is different. What’s at stake in ‘Deadpool’ is love. Just when it looks like Ryan Reynolds’ Wade and Morena Baccarin’s Vanessa have found their perfect match – he does allow her to take him up the ass on International Women’s Day – he is struck down by cancer. Then, when he thinks he is going to be cured, Francis fries his flesh and he can’t bear the thought of allowing Vanessa to see him that way. And finally, Francis kidnaps Vanessa to use her to get to Wade. The final climactic battle isn’t Deadpool trying to overcome impossible odds to save the world; it’s Deadpool trying to kill the man who made him look like a giant angry avocado. If, as an exec, you’re used to watching the Avengers fight an impossible swarm of aliens or the X-men battle a god, then what is at stake in 'Deadpool' must seem pretty paltry. But, as Reese, Wernick and Goldsmith discuss, after a $260 million opening weekend, it didn’t seem paltry to the audience. The problem with most stories isn’t what’s at stake - most writers seem to understand that the hero’s life, the life of someone he/she loves or his/her entire way of life is a good place to start – the problem is how to raise the stakes. If a story starts with a mother struggling to scrape together enough money to pay for her son’s operation, the stakes at the outset are pretty high, so how do you raise them? I have always thought that Martin Brest’s 1988 film ‘Midnight Run’ is a masterclass in how to raise the stakes. Robert De Niro plays a bounty hunter who dreams of getting out of a business in which he is always being shot and sworn at so he can open a café. He thinks the opportunity has arrived when he’s asked to find Charles Grodin’s Jonathan Mardukas. Mardukas stole $15 million from the Chicago mob, gave it to charity and then went into hiding after getting a bail bond company to pay his bail. The company, run by Eddie Moscone, played by the constantly excellent Joe Pantoliano, wants Mardukas found and brought back to LA or it’ll lose a quarter of a million dollars. De Niro’s Jack Walsh has five days to complete the task. As with any good story the setup is simple: a main character with a very clear idea what he wants and a time limit in which he must achieve it. And, as with any good story, things start to get complicated immediately: the FBI, who are also looking for Mardukas, descend on Jack and warn him to steer clear because he’s only going to get in their way. Yaphet Kotto’s Agent Alonzo Mosley threatens Jack in no uncertain terms. Dennis Farina’s mobster, Jimmy Serrano, also hears what Jack is up to and sends two goons to finish Mardukas off before he gets arrested and tells the police everything he knows about Serrano’s business. So even before Jack has found Mardukas the stakes have been raised: if he does what he’s set out to do he’ll either be arrested by the FBI or killed by the mob - his freedom and life are at stake. So how do you raise the stakes from that? Well he finds Mardukas and, understandably, Mardukas has no intention of going to prison because he knows Serrano’s people will kill him. From the outset Jack’s golden goose makes Jack’s life difficult: he fakes a fear of flying so they get kicked off the plane which was going to get Jack back to LA from New York in plenty of time. So, pursued by the FBI, the mob and an inept bounty hunter called Marvin, they have to make their way across the US by any means possible (apart from flying – until Mardukas tries to steal a plane!) They run out of money, food and transport. In every single scene Jack’s plan to get Mardukas to LA by midnight on a certain day so he can leave bounty hunting and open his cafe is tested to the extreme – just when the situation looks impossible, it becomes more impossible as first the FBI, then the mob, then Marvin try to snatch Mardukas away from Jack. But the genius of ‘Midnight Run’ is that it does not only rely on external stakes – having to outwit the FBI or dodge bullets fired at them by the mob – there are emotional stakes. Mardukas keeps telling Jack that Serrano’s men will eventually get to him, and, as hard as he might try, Jack can’t ignore the fact that he is leading a good man to his death. What's at stake is Jack's desire to always be on the side of good. Also Jack, who hasn’t seen his wife and daughter for six years since he was run out of Chicago by a corrupt police force who were all taking bribes from a drug smuggler, is forced to go to their house and ask for money. As soon as his ex-wife opens the door you can see he still loves her but she’s now married to one of the corrupt cops. Then his daughter offers him her babysitting money and it breaks his heart. And this leads to the ultimate stake for a man with a strong moral code like Jack, a man who wouldn’t take a bride, because Mardukas realises that the drug smuggler who ran Jack out of Chicago and Jimmy Serrano are one and the same man: if Jack does what he has set out to do he will, in effect, be helping the criminal who destroyed his life. An impossible situation just became more impossible because what is at stake now is everything Jack sacrificed, a wife he still loves and a daughter he misses, and everything he stood for when he wouldn't take a bribe. The fourth act of ‘Midnight Run’ ends exactly where a fourth act should: Marvin manages to snatch Mardukas away from Jack and Jack is arrested by the FBI. There is no way in hell, we think, is he going to come out on top of this situation. But then, as the story builds to its climax - and this is the only time it should happen - through the main character’s ingenuity, suddenly the impossible seems possible. Both ‘Deadpool’ and ‘Midnight Run’ raise the stakes in the same way: at the beginning of the stories the main characters are given what they want – in ‘Deadpool’ Wade finds a woman who is as deviant as he is and in ‘Midnight Run’ Jack sees a way to leave bounty hunting forever – and then what they want is taken away from them and they have to fight to get it back with each scene raising the stakes in some way - physically, emotionally, morally. But through the fight they discover something else: what they need. Me: ‘What is Forrest Gump’s motivation?’ Robert McKee: ‘To please his mother.’ Me: ‘?’ Those of you who have been to one of Robert McKee’s ‘Story’ seminars will know that the windows for Q&As are very limited: the beginning of the day, if you get there early enough, or at the end of a long day – no one is allowed to ask questions during McKee’s seminar. But in one of those brief windows I took the opportunity to ask a question that had puzzled me ever since I’d first seen Robert Zemeckis’ 1994 film in which Tom Hanks plays the central character and I thought if anyone would know it’d be McKee. But his answer didn’t seem to hit the nail on the head entirely. Of course, Forrest Gump’s mother, played by Sally Field, is a huge presence in his life, she is after all his mother, and she does, as all mothers do, everything she can to help him. But she has no specific plan for Forrest: she doesn’t hold up any particular people as role models he should aspire to (his dad went on vacation and just never came back); she doesn’t tell him that if he behaviours in a good and decent way he’ll get there in the end because she knows, as Forrest himself says, he’s not the smartest man; and, apart from sleeping with the school principal, she does nothing to manipulate events so Forrest will get ahead. She tells him early in the film that he is no different from anyone else – which isn’t a resounding call to action. She has absolutely nothing to do with Forrest’s talents, his ability to run fast and play ping-pong, talents that, contrary to every storytelling convention, he takes to like a duck to water with no training or struggle. When Forrest asks her what his destiny is, she tells him that he has to figure that out for himself. Then she dies. But perhaps the most important aspect of his life upon which she has no impact at all, because as far as we know he never tells her, is his love for Jenny. I always thought that if any one person was motivating Forrest Gump it was Robin Wright's Jenny. Jenny is the constant throughout Forrest’s life: from the moment they meet on the school bus when they are children, they are like peas and carrots. She sneaks out of her grandmother’s trailer to be with him and he sneaks into the single sex college to be with her. He writes to her every day he is in Vietnam and meets her again at an anti-war demonstration when he returns. He thinks of her as he lies under the stars, alone on his shrimping boat, and when he moves into his mother’s house. And it is there, unexpectedly, that she comes to him. They spend a night together and then she is gone again. When they do finally get together, it is only briefly, because she is dying. But not once, throughout all their meetings, which are defined by Forrest’s desire to protect Jenny from the world, does he make a concerted effort to find her or to follow her when she decides to go: it is just that through the tumult of world events their lives collide - but she always leaves and Forrest accepts it meekly. So even Jenny, the love of his life, doesn’t motivate him to do anything. The only person who motivates Forrest to do something is Mykelti Williamson's Bubba. Forrest makes a promise to Bubba that when Bubba has a shrimping boat he will be his first mate. But Bubba dies in Vietnam so Forrest buys a boat, names it Jenny and acts as captain. Only he completely fails to catch any shrimp – until a literal deus ex machina, the bane of any storytelling expert, arrives in the shape of a hurricane and conveniently decimates the shrimping industry. This lack of a desire to achieve anything means that Forrest Gump is essentially the same character at the beginning of the film, when he is nine years old having his leg braces fitted, as he is at the end of the film, when he sits down to await his son’s return from school. Of course, main characters who don’t change over the course of a story have always existed, most commonly in the Western. Alan Ladd’s Shane, Clint Eastwood’s the man with no name and Yul Brenner’s Chris in ‘The Magnificent Seven’ are all exactly the same at the end of the film as they are at the beginning. But they are all men who are motivated to do something - usually to bring order where there is disorder - and because they are motivated to act when no one else can they change the lives of everyone around them. Forrest Gump changes people’s lives - only not by design but by complete accident. This is most perfectly illustrated in the sequence where he runs across the USA. After Jenny has left him again, and in his own words ‘For no particular reason at all’, he starts to run. He runs to the end of the road, then he decides to run to the end of town, then across the state of Alabama and then all the way to the ocean. And because he’s managed to run that far, he turns around and runs all the way to the other ocean. And he keeps doing this for three-and-a-half years. Along the way he gives one man the idea for the ‘shit happens’ bumper sticker and another the idea for the yellow smiley face on a t-shirt. He doesn’t plan to and it only happens because he runs through some dog shit and then gets splashed in the face with mud. Ardent fans of the film will know that he also inadvertently teaches Elvis to dance and casually gives John Lennon the lyrics for ‘Imagine’. But he has no goal which he accomplishes before leaving; no enemy that he defeats before riding into the sunset. So maybe the answer to the question I asked Robert McKee is that Forrest Gump is a unique character who has no motivation, a character who is sustained by love, specifically his enduring love for Jenny – and over the course of the two-and-a-half hour running time of the film, across the span of US history, and contrary to every storytelling convention - that is enough… “You know, you were right,” my nephew said to me. “About what?” I asked. “Terminator is a better film than Terminator 2.” Finally, I thought. He had come to this revelation whilst being bedridden after an operation and watching James Cameron’s ‘The Terminator’ day after day. The debate as to which of Cameron’s killer cyborg movies is the best has raged since ‘Judgment Day’ was released in 1991. Of the 1652 people who voted in an IMDb Face-Off pole, 1206 chose ‘Terminator 2’; a survey of critics on Indiewire was split right down the middle; Terminator 2 is routinely cited along with ‘Empire Strikes Back’, ‘The Godfather: Part 2’ and ‘Toy Story 2’ as one of the few instances where the sequel is better than the original. The reasons why ‘Judgment Day’ is considered a superior film are that it has a better story, better effects and a better villain in the T1000. I must confess, I never thought ‘Judgment Day’ was equal to ‘The Terminator’ and the reason can be summed up in a single line of dialogue from each film. In ‘The Terminator’: Kyle Reese – ‘I came across time for you Sarah.’ And in ‘Terminator 2: Judgment Day’: The Terminator – ‘Now I know why you cry but it is something I can never do.’ At some point in the future John Conner gave Kyle Reese a photo of his mother and Kyle Reese became obsessed with it. Kyle tells Sarah about the photo, that he lost in a fire, and how he remembered every contour of her face and how he’d spend time wondering what she was thinking about at the moment the picture was taken. It turns out, at the end of the film, when a young boy in a petrol station takes the photo, what Sarah is thinking about is Kyle Reese. At its heart ‘The Terminator’ is a love story about two people who come together across time and create the messiah. The emotional heart of ‘Terminator 2: Judgment Day’ isn’t as sophisticated: through continued interaction with people, Arnold Schwarzenegger’s Terminator learns about empathy - something the people he and John Conner observe seem to have forgotten (‘It is in your nature to destroy yourselves’). ‘Terminator 2’ is essentially a machine’s coming of age story. But my nephew’s conversion made me think that maybe it isn’t a case of one film being better than the other but that the two films are for different times in a person’s life. When we are young, and the love of our close family is enough, we must learn how to empathise – to understand what other people are feeling and why – ‘Now I know why you cry but it is something I can never do.’ - but as we grow we all quest for love and hope that there is one person out there who will complete us because who wants to be alone – ‘I came across time for you Sarah.’ In a way, because it is a coming of age story, ‘Terminator 2: Judgment Day’ isn’t a sequel to ‘The Terminator’ but an emotional prequel. So if someone you know insists that ‘Terminator 2: Judgment Day’ is the better film and anyone who thinks otherwise is a fool (as my nephew used to), tell them to wait awhile because inevitably they’ll grow into ‘The Terminator’. “First things first; Jaws is not about a shark.” film critic Mark Kermode wrote in the opening of his 2015 ‘Observer’ article ‘Jaws 40 years on: One of the truly great and lasting classics of American cinema’. Anyone familiar with Kermode’s BBC Radio 5 Live film show with Simon Mayo will know that he is fond of telling listeners what he thinks Jaws is actually about, namely infidelity. The question ‘what is a story about?'’ fascinates everyone because a story has to be about something. But there is a common lament amongst people who read manuscripts, books, plays and scripts for a living: ‘It was okay, but it wasn’t about anything.’ And that is clearly a problem. Kermode goes on to list various potential abouts that were debated at the ‘Jaws 40th Anniversary Symposium’ at De Montfort University in Leicester: ‘masculinity and crisis in Jaws’, ‘Jaws and eco-feminism’ and ‘Jaws: the case of the archetypal American villain as queer dissident attacking the heteronormative.’ These theoretical debates that take place once a story has been told are, of course, essential and interesting to academics but are completely and utterly irrelevant to a storyteller. So, for a storyteller, if Jaws isn’t about infidelity, which it clearly isn’t, and it isn’t about a queer dissident’s attack on the heteronormative, which is debatable, what it is about? To understand, you must first understand why we tell stories at all. Back in the days of yore, long before scholars set down the tales of Gilgamesh and Beowulf, the world was full of mystery and danger and the only way to make sense of the noises in the night or the lights that shot across the sky was to use your imagination. Those with the most fertile imaginations seemed to come up with the most plausible explanations: the noises in the night were monsters that would come and get you if you were bad and the lights in the sky were the creator’s anger. Over time, and through retelling, these seeds grew like any organic thing and became stories: the noises in the night became ‘Beowulf’ and the lights across the sky became ‘The Bible’. But what they never lost, in all the millennia they have been told and retold, is the germ of their inception: to make sense of the world. Whether they do it as a grand gesture – Tolstoy’s ‘War and Peace’ – or simple allegory - Orwell’s ‘Animal Farm’ – all storytellers continue to be motivated by this simple ambition. So what aspect of the world is Jaws trying to make sense of? Well Kermode is right in his opening statement: Jaws isn’t about a shark. The shark in Jaws has more in common with Melville’s ‘Moby Dick’ than it does to any real shark: it is vengeful and determined in a way that no real shark would be. So if it isn’t a real shark then it must be a monster, because it is terrifying and destructive like all good monsters are. And the universal truth about monsters is that they don’t exist. Monsters are always physical manifestations of the hero’s weakness and we know, because it is repeated throughout the beginning of the film, that Martin Brody’s weakness is that he is afraid of water. He is afraid, it is his defining characteristic, and when you look closely you realise that everyone around him is afraid of something: Hooper, the rich city boy, is afraid of not being taken seriously, the mayor is afraid of what will happen to his reputation and career if he closes the beaches, Ellen, Brody’s wife, is afraid of losing her family and the most wonderful manifestation of fear is Quint. Quint ends the monologue in which he describes watching his shipmates being eaten alive after a Japanese submarine sinks the USS Indianapolis with the statement that he’ll never put on a life jacket again: Quint is afraid of fear itself. In the first half of Jaws, Brody gives in to his fear: he remains on dry land while he gets others to hunt the shark. Halfway through, after the fishermen have caught the wrong shark and the patrol around the beach miss the shark because two boys cause a distraction, Brody realises that the only way he is going to defeat his foe is by following it into its lair – which is the thing he is most afraid of: the ocean. Once he is on the boat his fear is emphasised: he wears a life jacket and he refuses to climb out to the edge of the boat to give Hooper perspective. And things go from bad - ‘We’re gonna need a bigger boat.’ - to worse: Quint destroys their radio, the boat starts to sink, the engine explodes, they think they’ve lost Hooper when they pull his diving cage back up and it’s all mangled and then he has to watch Quint being eaten alive. All of which would traumatise any normal person never mind someone who was already afraid of water. And yet the experience has the complete opposite effect on Brody: instead of feeling that his fear was justified, his fear is vanquished: ‘I used to hate the water,’ he says, as he and Hooper swim back to dry land. ‘I can’t image why,’ Hooper responds. We are all afraid of something – whether it is an irrational fear like being afraid of water, a contemporary fear such as not being taken seriously or losing our job, or a primal fear like losing our family – and the only way we can overcome our fears is not by giving in to them or letting other people deal with them but by facing them. That’s what Jaws is about: fear and how we overcome it. |

ScriptPlayerWriter, reader, pontificator. Archives

May 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed